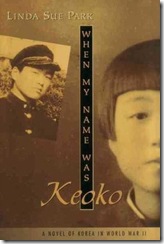

When My Name Was Keoko, by Linda Sue Park

I really, REALLY liked this book. I know I'm ignorant of Asian history, but until I read this book I didn't realize how much my ignorance mattered. When My Name Was Keoko showed me that the Japanese occupation of Korea in the first half of the twentieth century was not only an attack on the Korean government and military, but on Korean culture and identity as well.

Sun-Hee is a young girl living with her family in Korea during the Japanese occupation of her country in the years before and during World War II. For decades, the Korean people were not allowed to be Korean:

"A long time ago, when Abjui was a little boy and Uncle just a baby, the Japanese took over Korea. That was in 1910. Korea wasn't it's own country anymore.

"The Japanese made lots of new laws. One of the laws was that no Korean could be the boss of anything. Even though Abuji was a great scholar, he was only the vice-principal of my school, not the principal. The person at the top had to be Japanese.

"All our lessons were in Japanese. We studied Japanese language, culture, and history. Schools weren't allowed to teach Korean history or language. Hardly any books or newspapers were published in Korean. People weren't even supposed to tell old Korean folk tales.""

Every day is a struggle as the family must balance submission and defiance in order to survive while retaining their identity as Koreans. New laws are passed requiring all Koreans to adopt Japanese names; Sun-Hee becomes Keoko. Korean is no longer permitted to be spoken in public. Symbols of Korean culture and tradition are destroyed. Koreans must demonstrate complete loyalty to the Japanese Empire and its emperor. Yet Sun-Hee and her family find ways to hold on to their identity, and to defy the tyranny of their oppressors.

Unfortunately, this is a pattern that has repeated itself countless times throughout human history. The state defines what a person should think, how a person should be, then methodically eliminates the former ways. Language, culture, religion, and tradition are deliberately supplanted with a state-defined identity. Suppression is justified through a pretense of moral superiority, enforced through implication of violence, and legalized through corrupt legislation. Schools cease to be places of education to become places of indoctrination. It's happened so often that I must assume it's human nature.

What happened in Korea falls on a spectrum of cultural suppression. Look on the more extreme end of the spectrum and you'll find ethnic cleansing and genocide. Look on the less extreme end of the spectrum and you'll find what's happening in the United States today, where public institutions are commandeered to serve as tools of social engineering. Interpretations of the law are routinely stretched to impose a state-defined sense of morality, to promote a particular way of thinking rather than to protect one's right to believe as one chooses. Schools have been similarly hijacked. For example, the primary purpose of history class is no longer to inform students of how our society came to be, but to instill a particular value system in our children's world view. Even if I agree with the values being taught in the schools - and in general I do - this isn't the school system's right or responsibility. Far too often, public school attempts to be a secular Sunday School.

I don't think most people recognize the degree to which our government is adopting - and enforcing - social dogma. And I don't think most people recognize the danger of allowing the state to do so. This is why the book seemed so relevant to me. Our country's use of laws and schools to promote a social agenda may be benign when compared to the holocaust, but it is on the same path. There is such a big gap between modern America and Nazi Germany that you may not see the connection. See what falls in between and it's easier to see how you could get there from here. Take a good look at today's society and it may look more like 1930's Korea than you would have guessed.

5 stars

No comments:

Post a Comment